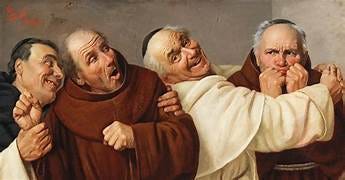

Ah, the monastery: peaceful cloisters, rhythmic chanting, gentle clinking of prayer ropes—and absolutely zero disputes about whose turn it is to unload the dishwasher. For those of us who live somewhere between the austere silence of Mount Athos and the perpetual chaos of domestic bliss, mastering the elusive "life-wife balance" can be trickier than solving the Filioque controversy over breakfast.

Take, for instance, Brother Basil—known to his wife as Brian. By day, he's steeped in hesychasm and St. Gregory Palamas. By night, he's desperately trying to remember whether his wife asked him to buy almond milk or oat milk with the weekly shopping, all the while contemplating the mysteries of uncreated light. His life oscillates precariously between profound contemplation and perilous forgetfulness. Brother Brian typifies a life-wife imbalance: having emphasised “life” too much, he must deposit four-fold into the “wife” column to adjust the deficit.

Then there are the issues harrying Br Basil’s attempts to reconcile accounts. As do many would-be monastics, Br Basil has an elevated sense of his own capacity for accomplishing the infinite list known as the “honey-do.” He begins the day with Herculean pronouncements: the twelve labours shall be accomplished! These promises usually effect an effort more akin to those of Goliath the Philistine who—despite his incomparable size—was felled by the simplest device. In Basil’s case, he forgot to pick up the oat milk.

Brother Basil has conquered the Philokalia, he's fluent in Koine Greek, but he's still perplexed by that one crucial text: the "You-know-what-you-did" message from his wife. No amount of Patristics can quite prepare you for this apophatic marriage theology, where the divine silence is not only mystical but it is also a geometrical act of remembering which conversation connects to which previous one and to which others and back again, thus enclosing his failure in a polygon of matrimonial meaning. In Brian’s case, too much life and too little wife has weakened his nuptial virtue, leaving him incapable of even answering the purportedly simple question, “What’s wrong?”

Let’s not forget long-suffering Deacon John. He emblemises the too-much-wife direction that routinely backfires. Deacon John has a liturgical soul. His impromptu thoughts on humility in politics draw literally tens of likes on Facebook. But his grace is most rigorously tested by his inability to fold laundry according to the rubrics set forth by his beloved. No ascetic discipline compares to performing feats of sartorial yoga under the watchful eye of a homespun Marie Kondo. The result: frustration, sighs of disapproval, and Mrs Deacon John just doing it herself.

In the monastery of his mind, Deacon John once envisioned meticulously scheduled days, each hour filled with scholarly productivity and spiritual discipline. Reality, however, introduced him to the profound theological mystery known as "Where did the day go?" A man who once confidently outlined the complete works of Augustine in 1000 words now humbly acknowledges that just making it through the honey-do list intact is a miraculous feat worthy of canonization.

Deacon John once dreamed of a solitary life spent in rugged asceticism, his days structured by fasting, prayer, and chanting Psalms in the Skete before the sun rose. Instead, he finds himself vowing each morning to heroic house-mannery: repair the sink, mow the lawn, organise the garage, sort the recycling to avoid another fine, pay the bills, fix the squeaky door in the kids’ room, get the oil changed, and still find time to shop, cook, and lead evening prayer with his family. He might chant Psalm 51 with tearful sincerity, but even King David never faced a honey-do list to make a Desert Father tremble. By promising too much and delivering too little, John satisfies neither the “wife” nor the “life” dimension of life. In short, he has a classic life-wife imbalance.

Then there is Brother Gregory, the idealist and meticulous planner, determined to strike the balance right. Each morning he resolves to respond patiently and calmly to every domestic challenge. By evening, he finds himself repeating the Jesus Prayer—not merely for spiritual elevation but as a necessary mantra to prevent spirited words leaping from his mouth when toothpaste-tube etiquette or thermostat settings are brought to his attention.

Armed with spreadsheets and to-do lists, Br Gregory confidently anticipates each day’s challenges. Yet, he routinely finds himself mystified at how all plans unravel spectacularly by lunchtime. His strategic brilliance at handling multi-tiered theological debates on the economical Trinity somehow does not translate into navigating familial logistics, leaving him perpetually astonished and humbled when Mommy comes home. Thomas Merton might have said, “Every man secretly wants to be a monk.” He would have said it had been a Christian husband like Br Gregory rather than a Trappist monk.

So how does one achieve the elusive “life-wife balance”? Firstly, understand that monastic obedience pales next to marital compromise. Yes, silence is golden—but so is remembering anniversaries. Sure, hesychia (holy stillness) leads to inner peace, but so does learning the subtle difference between your wife's “Fine” meaning “Everything is perfectly agreeable” and “Fine” meaning “Could we talk?”, and “Fine” meaning “I’m never going to talk to you again (or at least today)”.

The Fathers of the desert may have fled into solitude to seek divine union, but for those of us married monastics in the world, divine union often involves less fleeing into solitude and more fleeing into the garden shed to allow tempers to cool.

Paradoxically, in navigating the life-wife balance, one encounters perhaps the most profound spiritual truth: holiness lies not merely in silent vigils but in lovingly enduring,"Honey, can we talk?" at precisely the moment the spirit calls us elsewhere. Like every good married monk, the answer is, “Of course, my love.”

In the end, maintaining the life-wife balance is much like spiritual warfare: it demands vigilance, a good dose of truth telling and repentance, and a good sense of humor. And maybe—just maybe—this delicate dance between contemplation and chaos is exactly where sanctity is forged.

Jerome St Jerome is in the archives sorting out some difficulties presented by his translation of the Book of Romans.